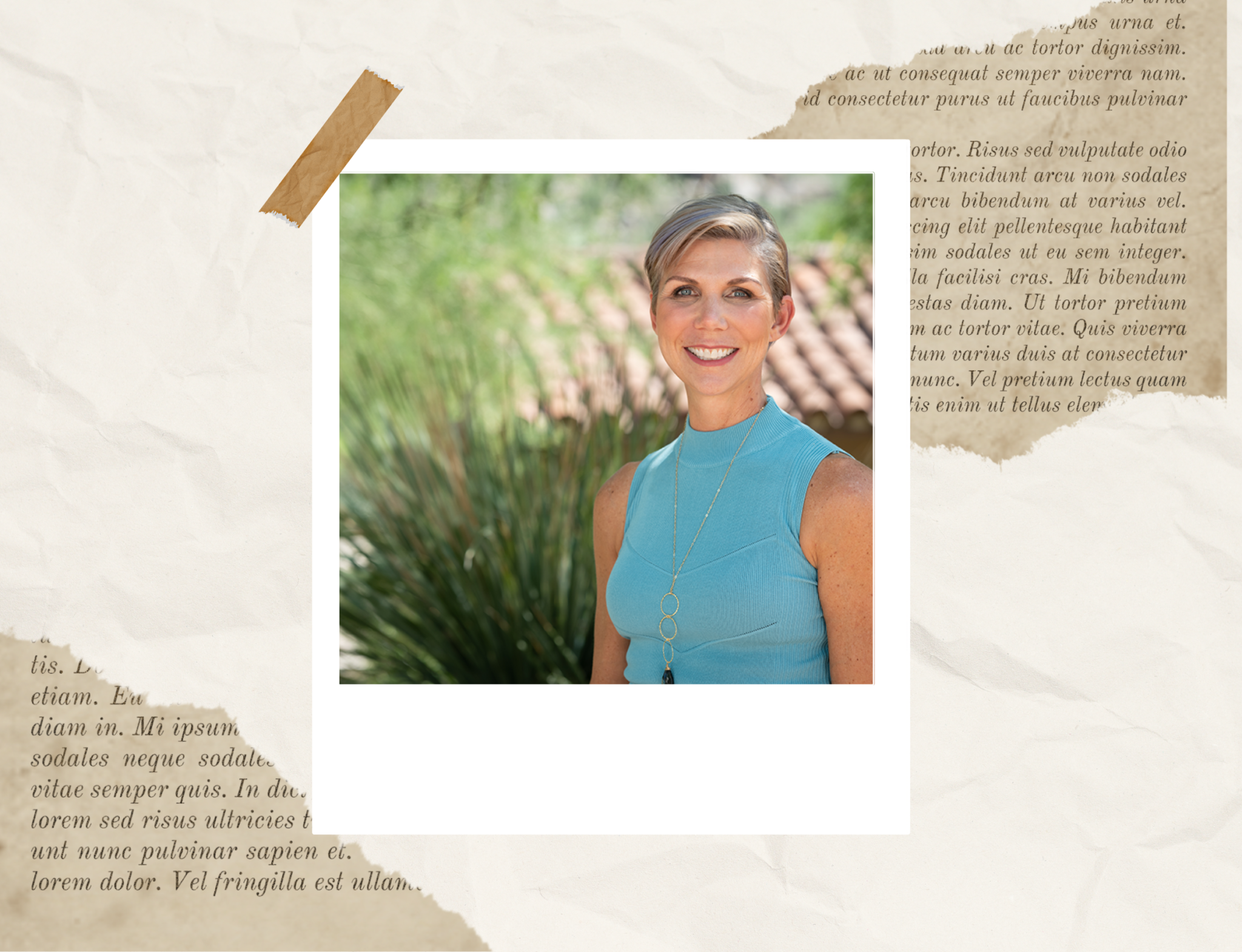

Wazhma Frogh is a women’s rights advocate and peace-builder. She co-founded the Women and Peace Studies Organization in Afghanistan — one of the few civil society organizations working for local peace building with community peace-builders. Wazhma is the 2009 recipient of the International Women of Courage Award — presented to her by then Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton, and First Lady Michelle Obama. She exemplifies the important role that women play as peacekeepers, when invited to the table.

You have been an activist for women, something that has been historically dangerous in Afghanistan. What drew you to taking up the mantle for women at a young age?

I grew up in a large family in Kabul shortly after the Soviets had just invaded Afghanistan. In my family, the expectations of women were very straightforward and traditional. But I always had an independent spirit. I remember breaking the rules and neglecting my house chores so that I could play with my male cousins which didn’t go down well in my family. I was the only girl child in my family that was breaking the rules.

When the civil war started in Afghanistan in 1989, my family had to flee to Pakistan and things got serious under the Taliban. It was a difficult time for girls — my sisters and I worked harder than my brother to go to school. My father was a traditional man and didn’t believe that women should be educated. I think my early years spent rebelling against those early house rules translated into that drive to educate myself and my sisters, and it shaped my outlook on women, their barriers, challenges and the possibilities.

Working with local peace builders changed my world view on how women can contribute to Afghanistan’s peace process.

What is the role that women can play in furthering the peace process?

Under the Taliban, we heard a lot about the brutalities against women, but we didn’t really know what we could do to help or how the situation could change. In 2001, I came back to Afghanistan and for the first time remember seeing hope in the hearts of the Afghan people. I was part of one of the largest women’s movements in the country, and we organized initiatives to bring women into government and peace processes.

At the time, President Hamid Karzai was appointed to convene a Constitutional Loya Jirga to draft a new constitution. I worked with UNIFEM (part of UN Women) and my job was bringing women’s voices and views to the table. I went around provinces all over Afghanistan and would talk to women about their issues. What amazed me, was that women had a solid understanding of the issues in their communities or villages, but more importantly, they had substantive solutions.

This was at a time when Afghanistan and Pakistan had a difficult relationship and we constantly heard from men that Pakistan was the root of conflict. Women on the other hand, approached the problems constructively. They knew firsthand about issues in schools, hospitals and in their local governments. Their solutions were more grassroots, their approach was to tackle the problems from the ground-up. That’s when I understood that women bring lots of solutions, even though they are the ones not fighting. They can make a big impact on national processes and help bring peace to Afghanistan. The Constitutional Jirga changed my world view on how women can contribute.

You co-founded the Women & Peace Studies Organization in Kabul. What were some of the challenges for a women led peace organization and can you talk a little bit about the work you have done?

When I returned from my masters in the UK, I started the Women and Peace Studies Organization together with a then member of parliament. I was an activist for women and well known in the community, and I remember the reactions of people when we registered the organization.

Most people couldn’t understand or even accept that women had a role in the peace process. So, we went back to the provinces to speak to local women. Some of them were elders in their community. Most of them were illiterate – they were literally sitting under trees talking to us about peace building. But despite being illiterate, they were able to influence local conflicts. And the reason is that when local conflicts are addressed through non-violence, culture around conflict, war and peace shifts. People can envision what peace looks like. Before this, conflict was resolved with violence. Afghanistan was at war for over thirty years so people were used to violence as a tool to solve problems.

When local conflicts are addressed through non-violence, culture around conflict, war and peace shifts.

We started to do more community-based work with women peace-builders as part of the WPSO’s Conflict Resolution Program. They would intervene at their local jirgas (local tribal council) that were making decisions on life and death matters and introduce peaceful resolutions. As an example, traditionally, a conflict between two families was resolved through violence, depending on the severity of the crime. These women started to introduce measures like fines and community service instead. Though this seems like a small change, the mindset of communities shifted towards non-violence through these measures, and that had a big impact.

How has local peace-building informed the national peace process or talks with the Taliban? Do you think the Doha peace deal with United States will improve the situation for women?

That’s been a large focus of my work through WPSO. But also as a senior core member of the Afghan Women’s Networks for years, I have engaged in national and international campaigns for women’s inclusion in peace processes. Through our engagements in the international community, we formed coalitions of women where we applied the lessons learned on the ground to advocate for women’s inclusion in peace building.

There are a lot of gaps in the current peace deal signed in Doha in 2019. It lacks an understanding of the root of conflict in Afghanistan. It allows the US to reduce its military presence in the country, but where does that leave Afghanistan? Will this leave space for international terror groups to gain a foothold in the country? A peace deal is not simply talks with the Taliban and withdrawing troops. It must include a reconciliation process. Afghanistan has many war lords — is there a transition justice process? How do we rehabilitate our youth? Is there a disarmament and reintegration process? Who will do this?

In July I presented to the UN Security Council and posed these questions – what happens if the current peace talks fail in Afghanistan? Will there be another US war in Afghanistan or millions of dollars poured into the country in aid? The current deal simply allows President Trump to show his constituents that he has brought troops home before the November election.

In how this impacts women, if the Taliban gain a strong foothold in the country the situation will worsen for women. Women have made progress in the last 25 years. We have women in government, business, women diplomats, entrepreneurs and the Taliban has always maintained a clear position that they are not in favor of this. Does this mean women will be banned from participating and working? Or if not, what are the guarantees for women in areas that are under Taliban control?

My organization looks at women’s conditions in regions under militant control and there is still a lot of violence in those areas. They are forced to stay home and can’t even visit the doctor. If there are no plans to withdraw these militants and rehabilitate the community, these women will be under a brutal regime. The U.S. wants to leave Afghanistan back in the hands of the people, but the deal needs to address these major issues and include them in the peace process.

What are some of the effective ways in which women can negotiate with leaders and progress their rights?

Afghanistan is a predominantly Muslim society, and religious clerics play a major role in all aspects of civil society. For women to progress their rights, they need to understand religious texts, theology, and the language of religion. Sadly, across the Islamic world, there aren’t many female religious scholars that come from a position of authority. Negotiating with the Taliban is a different case, however. The Taliban don’t just speak the language of religion, they speak the language of violence. Their interpretation of religion is extreme. So, although there are many women studying religion in Afghanistan, it is very risky.

The moment a woman talks about religion or interprets it, she opens herself up to attack. It’s a complicated subject because a strong understanding of religion is what women need to further their rights and unfortunately the gatekeepers of religion are men who don’t want to see that happen.

You have faced many challenges working in this space, including threats to your security and life. Can you talk a bit about how you managed to endure despite these challenges?

The challenges started quite early within my own family. I had an uncle who stopped talking to me the first time I appeared on television. The only man that has supported me is my father when he realized I can contribute to the family. He understood the importance of my work.

In 2013, my organization documented human rights violations of a local commander in one of the provinces. When we reported it, he lost a major contract. This made things difficult and I lived in hiding for six months. Eventually, I apologized to him in a jirga. It was one of the most challenging experiences of my life because I was forced to publicly go back on my convictions.

Despite the threats I have faced, and even though I had to leave the country for a while, I continue my work with the WPSO. I have never lost my convictions about furthering women’s rights, so that has helped me persevere. I do a lot of advocacy through conferences and social media and am currently working with The Coalition of Women for Peace by the Afghan Women’s Network, engaged in an international campaign — Afghan Women Won’t Go Back. The campaign has mobilized support from the international community for an inclusive Afghan peace process.

Women share a common global language — we want peace and happiness for our families, children and communities. We face different challenges, but the root of our desires is the same.

How can women in Canada and the US be allies for women in Afghanistan?

I think unfortunately, the world does not know a lot about Afghanistan. What they do know is through a lens of war and violence. The narrative around women has been that we are victims. Throughout my career, I’ve highlighted the fact that women in Afghanistan have similar dreams to women anywhere else in the world. Women share a common global language – we want peace and happiness for our families, our children, and communities. We face different challenges, but the root of our desires is the same. Violence against women is not just an Afghan problem, it’s a global problem. And solidarity starts when you start knowing people. Once you start to think of Afghan women as people with dreams, not victims, you better understand the issues and them.

Wazhma Frogh has worked in both government and non-governmental institutions. Her experience includes Acting Director of Gender & Human Rights Directorate, and Senior Advisor in Security and Human Rights for the Afghan Ministry of Defense; Senior Advisor to the Minister (Ministry of Defense) and Deputy Chief of Staff to the Afghan Ministry of Interior. She served as a councilor on Afghanistan’s High Peace Council in 2017 and 2018.

Wazhma has advocated for women and children since she was a young girl, living and working in refugee camps in Peshawar, Pakistan. She is the 2013 recipient of the Amnesty International Award and has received accolades and recognition within Afghanistan for her work.

Wazhma is extensively trained in gender, peace, and conflict studies both at Harvard in the United States and the University of Uppsala in Sweden. She received the 2017 Women Peacemakers Program fellowship at the University of San Diego’s Institute for Peace and Justice.

For more perspectives from women in Afghanistan, read The changing face of women’s progress in Afghanistan