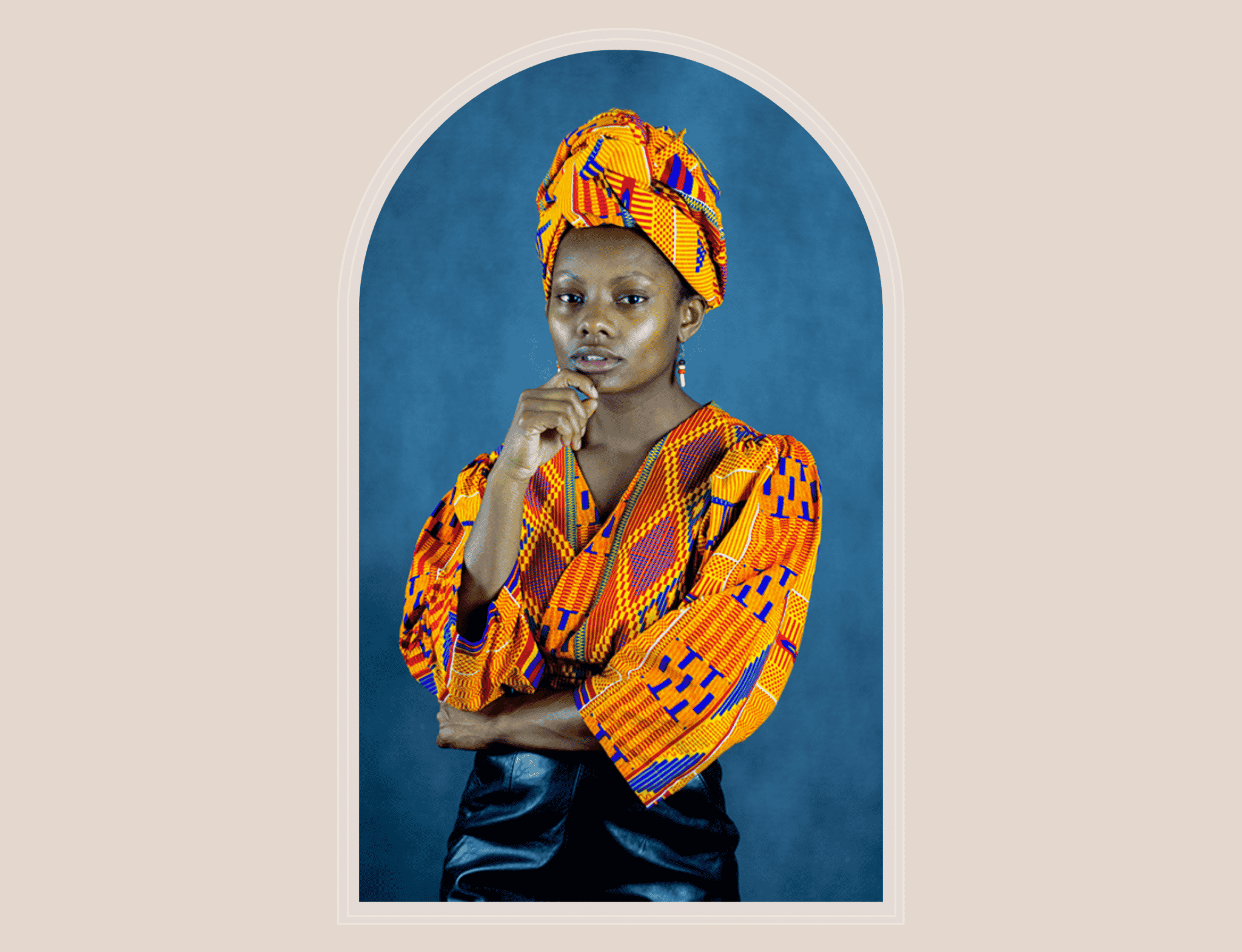

What does human trafficking look like? Have you ever met someone that is being trafficked or is a victim of trafficking? Chances are if you have, you wouldn’t know. They themselves may not know.

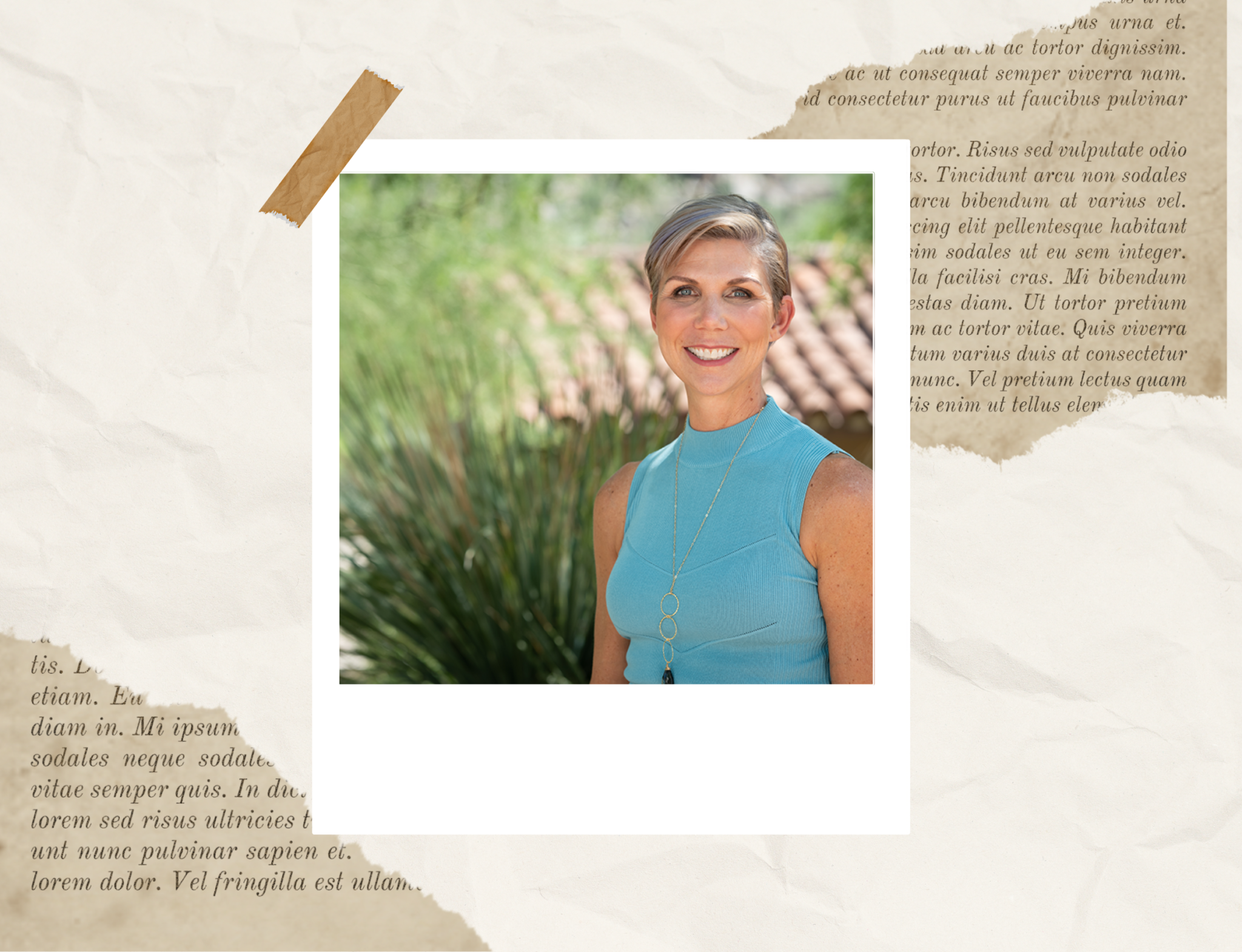

Rhonelle Bruder is a speaker, human rights advocate, and founder of Project iRISE (formerly the RISE initiative), a non-profit organization committed to educating and empowering at-risk youth and survivors of human trafficking. She is also a survivor of sex trafficking herself. Many years on from her harrowing experience, she has two post-secondary degrees and a successful career in Toronto’s healthcare system. She is raising a beautiful daughter and using her voice and experience to advocate for some of the most vulnerable people in our society. We connected over a socially-distanced coffee, so she could tell me her story.

Let’s go back to the beginning. Can you tell us a little bit about your story?

My story starts in St. Vincent and the Grenadines, a small Caribbean island nation. At the age of 3, I was adopted by a white Canadian family and moved to London in Ontario, a very homogeneous city especially in the late eighties and nineties when I was a kid. As a young child, I faced a lot of bullying and anti-black racism. This was a time when being different was not something to be desired. We didn’t have the social awareness we do now, to celebrate diversity and differences, so a Black girl adopted by a white family really stuck out.

I had two very loving parents, but they struggled with their own mental health issues. Although they did their best, they couldn’t provide attention and support to a child growing up with the issues I was dealing with — racism, discrimination, and a lack of belonging. At the age of 16, I left home and moved to Toronto where I ended up couch surfing, sleeping on the streets and eventually in the shelter system. It was at this precarious time in my life, that I was lured into the sex industry and trafficked in strip-clubs across Ontario.

Did you know or realize at the time that this was a dangerous situation or that you were being trafficked?

My situation went on for a few months and became quite dangerous, but you must remember, this was 20 years ago. We didn’t have the awareness that we do today around sex trafficking, so while I knew the situation was risky, I never considered myself a victim of trafficking. I just thought that I had made some bad decisions and had gotten involved with the wrong people. It was a type of internalized blame (which is common among victims of sexual abuse and trafficking) and there weren’t resources readily available to identify and support victims.

What was the turning point in this for you that put you on a path to getting out?

Eventually I got pregnant with my daughter at 18 and that’s when my situation became dire, because I was a single mom, living on welfare with a baby. I was out of the sex industry, but I was living in poverty as a high school dropout. There aren’t a lot of opportunities or jobs for someone in that situation. That was my rock bottom and I didn’t want that cycle to repeat itself with my child. That’s when education became my path out. I had grown-up believing that education was the way to a good future, so I went back and got my GED, completed my undergrad in Health Administration and eventually did my master’s in Health Informatics.

What does sex trafficking or human trafficking look like in Canada?

When people think of human trafficking, they typically think of images like from the movie Taken — someone being moved trans-nationally and sold across borders. In Canada, human trafficking and especially sex trafficking is still coercion and using someone’s body for financial gain, but it might not include transporting someone internationally or even domestically. Someone could be trafficked and be living at home. What we typically see is a relational interaction — a young woman or girl meets someone who likes her, flatters her. It might even be a boyfriend or trusted friend in that young person’s life that is forcing them into the industry by emotionally manipulating or holding something over them. Since this can lack the physical aspect of violence or abduction, it’s not always easy to identify someone as a victim of trafficking. It’s a psychological hold that the trafficker has over someone, which can be used in combination with physical force to coerce them but not always. It’s insidious and well-disguised so it’s not always obvious. An example are these sugar daddy websites where young women think they understand what they are getting into, and before they know it, they are forced into something they don’t want to do.

We need to shift our thinking around what victims of human trafficking look like. It could be someone in the Uber Pool next to you or someone who lives down the hall in your condo building.

What in your opinion or lived experience is the biggest misconception we have about trafficking in Canada?

I think the biggest misconception is what human trafficking victims look like, and the media is partially responsible for promoting a narrative of extremes. Most images you see of trafficking victims are people broken, beaten and in chains — problematic imagery that grabs your attention. But those are very extreme situations. That’s not what every trafficking victim looks like. Many victims are people you might even interact with day to day —in clubs, beauty salons, massage parlors and of course more vulnerable workers in the sex industry. Sometimes, the victims don’t even realize that they are being trafficked, because their trafficker is someone close to them. We need to shift our thinking around what victims of human trafficking look like. It could be someone in the Uber Pool next to you or someone who lives down the hall in your condo building.

The other problem is that there is a misplaced sense of glamour around the sex industry — again from movies. Hollywood has been portraying the wealth and glamour around the sex industry for decades — high end strip clubs, casinos and escorts who get paid a lot of money for a night with a billionaire. I remember the first time I went to a strip-club, the women were beautiful and fit, there was music. It was more like a night-club than a strip club. It didn’t look seedy, it looked glamorous, but the reality is that it is seedy, and it traps vulnerable women in a cycle of exploitation.

Let’s talk about Project iRISE. What motivated you to start Project iRISE in 2018 and how does it support victims of trafficking?

It was when I started volunteering in Toronto with at-risk-youth. I was taking some time off to complete my masters and working with vulnerable youth. I realized how much they reminded of myself and how little had changed in the 20 years since I was in a very unstable situation. I shared my story with them, and they were so shocked that I had pulled myself out, but at the same time they were hopeful hearing it. That’s when it clicked—there is something magical about using your own lived experience to empower other people. I started doing life-skills workshops with at risk youth and through that started the RISE initiative (now Project iRISE). It was very much a grassroots project to support these kids. It led to speaking opportunities and training focused on human trafficking.

How have you kept the project going during the global COVID-19 pandemic?

COVID-19 has given me some time to step back and look at iRISE from a new angle my speaking engagements and advocacy work is on pause. We focused a lot on at-risk youth before but are now involved with survivors of human trafficking, because there is a gap in the market to empower and rehabilitate them. We have shifted our focus towards helping survivors with transitioning out of the sex industry and find meaningful and sustainable employment. There are organizations focused on crisis-management, that support people to help them get out of sex trafficking, but not many are focused on what comes after — the getting a job and moving on with your life part. I want to build a program where women can tap into their skills so that they don’t face the economic pressure that forces so many back into the sex industry.

A lot of your work and talks have centered around resilience. How do you tap into your inner resilience in times of extreme hardship?

I believe resilience is the number one skill we need to have, but like any skill, we need to develop it. When we talk about resilience, we think of it as bouncing back from adversity. But I don’t think of it as bouncing back, because once you face trauma, there is no going back. You are never the same person you were before, so for me resilience is about taking what you’ve learned and moving forward. I like to think of resilience as a toolbox that I can tap into at any time, no matter what hardship I am facing, and many of those lessons are from a very dark period in my life. But they are tools and skills that got me out of it and have stayed with me. I am who I am today because of the trauma I experienced when I was younger, and I can do what I do because of it. Something good always comes out of a bad or negative experience and it’s important that we try and remember that.

If you look at the root cause of many serious societal issues like gang violence, sexual assault, gun violence or drugs, it can be traced back to childhood trauma.

In your opinion, what are the biggest challenges facing young people and at-risk youth?

I think we all know that there is a mental health crisis in Canada and across the world and young people are at just as much if not more risk to problems as a direct result of poor mental health. All young people are vulnerable, but there aren’t resources to support the mental health of young victims of trauma. Any kind of trauma. If you look at the root cause of many serious societal issues, for example gang violence, sexual assault, gun violence, drugs, it is traced back to childhood trauma. If we can provide resources to young people to deal with trauma early enough, we can prevent many more serious problems later in life. There is a quote by Frederick Douglas that I am reminded of “It is easier to build strong children, than to repair broken men.” Most of our work as a society is set up to be reactive, but we need to work upstream and support young children , nine- and ten-year olds, before they start engaging in risky behavior.

Rhonelle’s knowledge and passion about helping victims of trauma and sex trafficking is abundantly clear, as is her wealth of knowledge on issues of sex trafficking and trauma. In 2019, she made a deputation to the Toronto City Budget Committee advocating for at-risk youth. In April 2020, she wrote an article titled The Kids Are Not Okay: COVID-19 has Increased Sex Trafficking and Exploitation Concerns, urging parents to be mindful of the increased risk of children at home falling prey to predators online. As our conversation winds down, I realize the thing that strikes me most about Rhonelle is an endless reserve of resilience. She is fighting a fight that has some of the world’s richest generals (the Jeffrey Epsteins) and some of the poorest, most desperate foot-soldiers on the opposing team. And yet she believes that it is possible to win. Rhonelle has a very special set of skills — they make her a nightmare for those that want to exploit young people, because they make her a dream for those that want to rise.